Union

minister of petroleum and natural gas Ram Naik told parliament on Wednesday

that there were limitations to supplying CNG as production from the Oil

and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) gas fields was declining. “Any

diversion of the committed supplies to the vital sectors like power and

fertiliser will affect them adversely,” he pointed out (Financial

Express, July 26, 2001).

“The real glitch is that there is simply not enough CNG to go around.

Did it occur to anyone to stock up on the fuel the minute the court issued

its orders? Of course not” (The Times of India, March 28, 2001).

Fact

MOPNG

is trying to project that an acute fuel crisis is about to hit public

transport. They have inflated demand projections of CNG much beyond the

estimates by Indraprastha Gas Limited (IGL) and argue that available gas

cannot meet this kind of demand.

This claim comes at a time when IGL fails to meet its commitment to set

up all the 80 CNG stations as mandated by the Supreme Court and falls

short of converting all the ‘daughter stations’ to ‘daughter-boosters’

to help keep uniform pressure for gas and reduce filling time.

MOPNG is silent on the fact that it is possible to increase allocation

for the transport sector. In the meantime more gas has been allocated

for affluent households in Delhi to substitute LPG that will not make

any impact on the air quality.

MOPNG has suddenly woken up to a new reality — that it has to ensure

long-term supply of CNG to the city. But it is also looking for an escape

route to avoid making such commitments. The ministry did not take the

Supreme Court orders of July 1998 to move the entire public transport

system to CNG, seriously. They had only considered buses but not the autos

and taxis which were also mandated to move to CNG. Surely 80 CNG stations

would not have been ordered by the Supreme Court if only buses had to

be catered to. (The real reason for the ministry’s slumber is, as

one senior official put it, “We did not expect the orders to be implemented.”)

The ministry has argued that it cannot supply the growing use of CNG by

vehicles. But there are several discrepancies in the CNG demand figures

given by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MOPNG) and the Indraprastha

Gas Ltd. (IGL). According to the Planning Commission, the ministry has

allocated 3.07 million standard cubic metre per day (MMSCMD ) that is,

24.76 lakh kg per day (one kg of CNG is equivalent to 1.24 standard cubic

metre) of natural gas for Delhi as follows:

Power: 2.60 MMSCMD (20.97 lakh kg

per day)

Delhi Vidyut Board (DVB): 0.84 MMSCMD (6.77 lakh kg

per day)

Pragati Power: 1.75 MMSCMD (14.11 lakh kg per day)

Others (which includes vehicles and households): 0.48 MMSCMD (3.87 lakh

kg per day)

According to the ministry, only an allocation of 0.15 MMSCMD (1.21 lakh

kg per day) has been made for vehicles. The rest has apparently been made

for households. It is now quite clear from the various estimates available

from the IGL and MOPNG that their demand projection has always remained

flawed and they are playing around with it to mislead everybody.

According to the submission of IGL on April 4, 2001 to EPCA,

While

the total demand of CNG from buses, autos and taxis in April 2001 was

1.00 lakh kg per day the supply capacity was 2.23 lakh kg per day38 (about

0.28 MMSCMD). In other words, according to this estimate, the current

demand then was only 51 per cent of the available dispensing capacity.

One bus consumes about 56.5 kg of CNG per day39. Therefore, if 10,000

buses were to run on CNG, the demand from buses only would be 5.65 lakh

kg per day (0.7 MMSCMD).

Supply by October 2001 would be 6.65 lakh kg per day (0.82 MMSCMD).40

Thus, there would be excess CNG available even after catering to all the

buses. Clearly availability of CNG as such was not a problem according

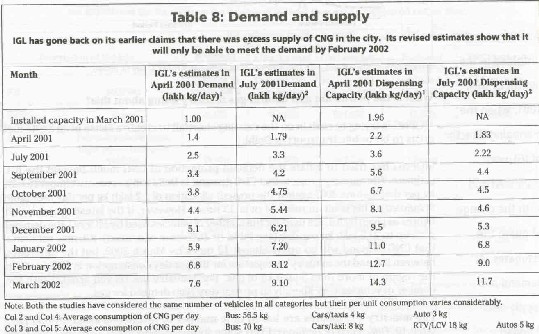

to IGL as on April 2001 (see table 8: Demand and supply).

Thus, demand and supply projections of IGL, made in April 2001, show that

the dispensing capacity will always remain ahead of the projected demand

till March 2002.

Around the same time, Ram Naik also pointed out that adequate quantity

of natural gas was available for the city. According to his estimates

presented to the media in the first week of April, there was supply of

1.96 lakh kg per day of CNG as against a demand of 0.95 lakh kg per day.

Thus, according to his estimates, the present capacity utilisation was

only of about 48.5 per cent.41

But

a new game unfolded in the month of July, 2001, when the former managing

director Rajiv Sharma was dismissed and with the change of guard the estimates

for demand

and supply also changed overnight.

Demand and supply projections of IGL, made in April 2001, show that the dispensing capacity will always remain ahead of the projected demand

In

its presentation to EPCA in July 2001, IGL revised its older estimates.

In the new estimates, they modified the consumption figures for all vehicles.

While according to the old estimates given in April a bus consumed 56.5

kg of CNG per day, the new estimate is that of 70 kg per day. The new

daily consumption estimate for cars and taxis was doubled from 4kg to

8 kg and that of three-wheelers from 3 kg to 5 kg.42

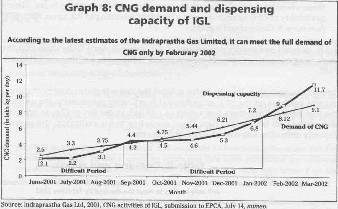

The consequence is that the July estimate shows that the dispensing capacity

will catch up with demand only in September 2001 once, slide back again

and then catch up once more in February, 2002 (see graph 8: CNG demand

and dispensing capacity of IGL).

What is the petroleum and natural gas ministry doing about this?

MOPNG

is trying to cash in on the existing shortfall to create a sense of an

acute fuel crisis to hit public transport in Delhi.

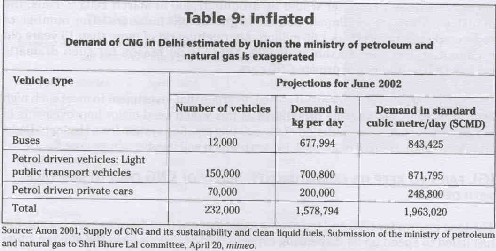

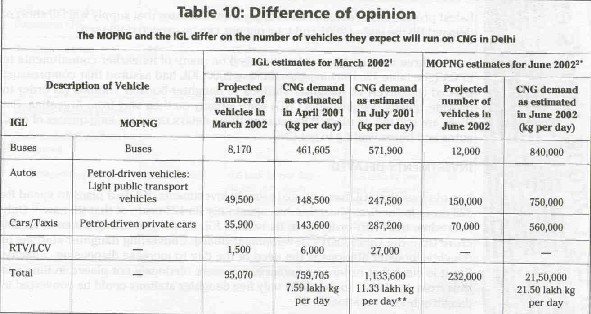

MOPNG has tried to inflate the demand projection of CNG much beyond the

IGL estimate. The ministry projects that CNG demand in Delhi will increase

to almost 16 lakh kg per day by June 2002 against the present allocation

of 1.2 lakh kg per day (see table 9: Inflated). This is an increase of

over 13 times. However, if the latest consumption figures as given by

IGL are used for the number of vehicles used by MOPNG, the demand goes

up to 21.5 lakh kg per day (see table 10: Difference of opinion). IGL

now estimates that CNG demand will go up by almost 12 times by March 2002,

but the difference between IGL and the ministry’s projection for

the per day consumption in 2002 is still in the region of more than 5

lakh kg of gas. The ministry has played around with the number of vehicles

very liberally to project very high demand for gas.

The ministry’s estimates are based on a number of erroneous assumptions

(see table 10: Difference of opinion). Even when three-wheelers (these

are the only light public transport vehicles run on petrol because taxis

run on diesel) were allowed to run on petrol their total registered number

in January 1999 was about 87,000.44 If the fact that no commercial vehicle

more than 15 years old are allowed to operate in Delhi is taken into account,

it would bring their number down to about 57,000. Even IGL’s estimate

puts

the number of three-wheelers at around 50,000 in March 2002.45 Therefore,

the estimate of the ministry is a gross overestimate for autos, almost

three times higher than the actual numbers.

The number of cars on CNG, according to the ministry, would be 70,000

in June 2002.46 This again is a clear case of exaggeration. IGL estimates

that the number of cars and taxis put together would be around 37,400

in March 2002.47 Thus, the ministry’s estimate is almost double of

the actual numbers. The number of registered taxis

in 1998 was 1.66 million. After getting rid of more than 15 years old

it cannot still exceed maximum 10,000. There is no reason for such dramatic

increase in the number of private CNG cars.

MOPNG has projected the demand so high to argue that investment to meet

such high level of demand will be quite prohibitive as this would need

major improvements in the system, including upgradation of the existing

pipeline system from Hazira to Dadri and Delhi (with a length of about

1,145 km), which will involve a huge cost.48

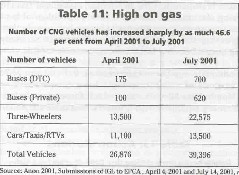

IGL fails to keep its commitments: Supply of CNG fails to keep pace with

demand

The long queues for CNG and harrowing experience of the CNG users are

legend. IGL has failed to speed up its dispensing capacity and supply

to meet the sudden surge in demand for CNG despite its commitments to

the EPCA. Once the Supreme Court made it clear that it would not entertain

any dilution of its original order, the CNG market that was sluggish initially,

picked up and within a very short time a large number of vehicles in different

segments rolled in (see table 11: High on gas). IGL was caught unawares.

People are only busy counting the numbers of stations. Even though as

many as 74 stations as against the original mandate of 80 stations are

in place it is the inadequate dispensing capacity and low pressure levels

in each of these stations that have compounded the problem.

Latest projections of demand and supply from IGL show that supply will

fall short of demand till the end of 2001 and long queues can be expected

till then.

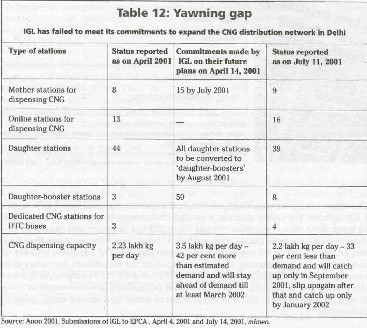

Just in three months IGL has backtracked on many of its earlier commitments

to EPCA (see table 12: Yawning gap). In May 2000, IGL had assured that

compressors needed to convert all daughter stations to daughter-booster

stations (in order to provide speedy dispensing of CNG) were already on

their way from Argentina. But these are still not in place.39 Because

of these delays there are long queues of cars, autos and buses waiting

to get CNG.

Investments

delayed

It

is obvious that IGL has not made timely investments. IGL had plans to

spend Rs 328 crore in the first phase but has spent only Rs 123 crore

of that till now.50 Only now when the court order is on its head is IGL

thinking of taking a loan of Rs 200 crore from the Oil Industry Development

Board. Converting daughter stations to daughter booster stations is the

need of the day to increase dispensing capacity. But it is clear that

orders for compressors were obviously not placed in time and thus from

April 2001 to July 2001 only five daughter stations could be converted

to daughter booster stations.

In the meantime the queues for CNG are getting longer and rarely do consumers

get a tankful of CNG. Why is this so? There are several issues related

to the supply of CNG:

a) Speedy supply at dispensing stations,

b) Long-term assurance supply of CNG, and

c) Reliability of CNG supply

Number

of dispensing stations

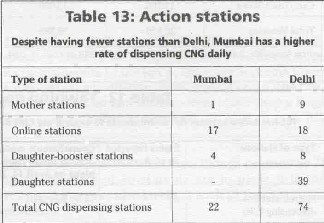

A researcher

of CSE who visited Mumbai in April 2001, found that while Mumbai was dispensing

one lakh kg of CNG per day through 22 stations,51 Delhi supplied 0.95

lakh kg of CNG per day through 68 stations,52 that is, over three times

the number of dispensing

stations than Mumbai. However, by June 2001, the daily sales in Delhi

went up to 1.92 lakh kg per day.

Mumbai also has long queues but this is mainly because of a large number

of vehicles, not the long time taken in dispensing CNG. In Mumbai, Mahanagar

Gas Ltd has to set up more dispensing stations but there is a serious

problem of land availability and there is not enough space in existing

petrol pumps because of safety requirements for CNG dispensing stations.

So why does Delhi with so many dispensing stations have long queues? Several

factors are responsible for this.

MOPNG’s projection of demand for CNG in Delhi is based on wrong assumptions and is almost double the estimate of IGL.

Latest

projections of demand and supply from IGL show that supply will fall short

of demand till the end of 2001 and long queues can be expected till then.

One factor is the lack of an adequate number of compressors.

In Delhi, out of 74 stations, 47 are daughter stations of which only eight

have compressors or boosters.34 In comparison, Mumbai has 22 stations,

of which there are only four daughter stations, all of which are equipped

with boosters (see table 13: Action stations).55

The biggest compressors, which are installed in mother stations, have

a flow rate of 1,100 kg/hour. For online stations, a smaller compressor

is used which can fill 250 kg/hour. Both these compress the gas up to

250 bar pressure and can serve two dispensers at one time, that is, they

can help to fill up four vehicles at one time (one dispenser is used to

fill two vehicles).56 Therefore, lack of adequate number of compressors

in a dispensing station can result in the dispensers becoming non-functional.

For instance, at the dispensing station near CGO complex, in spite of

there being five dispensers, all of them cannot be operated simultaneously

as there is only one compressor. IGL is in the process of installing a

second compressor in that station.57

There is another type of compressor called booster, which is used

only in daughter stations. The booster is used to increase the pressure

of the gas when the pressure in a cascade drops to about 180 bar from

the required filling pressure of 200-220 bar while dispensing gas. In

absence of a booster, it is not possible to dispense gas once the pressure

level falls to 180 bar, and then the cascade has to be changed.58 Cascades

full of CNG under adequate pressure are brought to a daughter station

after being filled at a mother station. A mother station is connected

to the pipeline.

A study on filling time of three-wheelers done by IGL in daughter stations

without boosters in Delhi showed that when the filling pressure is 200

bar, it can fill the cylinder of a three-wheeler to its full capacity,

that is, 3.5 kg in 90 seconds. But when the pressure drops to 180 bar

in the cascade, it can fill up to only 3.15 kg. It takes 67 seconds to

do so. At a pressure of 165 bar, the cylinder can be filled up to 2.89

kg only in 48 seconds, and at 150 bar only 2.63 kg can be filled up and

it takes 29 seconds to do so. At this pressure, it is not possible to

fill the cylinder any more and the cascade needs to be changed and replaced

with a new one.59 In other words, once the pressure drops in the cascade

of a daughter station, very little gas gets filled up in the vehicle’s

cylinder. This means that a commercial vehicle which runs all the day

has to keep coming back to a refilling station.

Number of cascades in a dispensing unit

This points out to another problem in the dispensing of CNG in

Delhi, that is, inadequate number of cascades in a daughter station. If

there are an inadequate number of cascades, then the dispensing station

will have to be closed till more cascades are obtained. While the daughter

stations in Mumbai have 3-6 cascades on average, in Delhi, there are less

than three cascades for each daughter station. There are 47 daughter stations

in Delhi and about 120-125 cascades. At a given point of time one cascade

is used, one is getting filled up at the mother station and one is in

transit. Not surprisingly daughter stations often have no gas to dispense

in Delhi.60

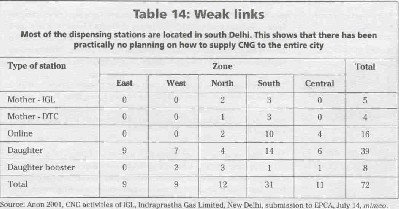

Distribution of dispensing stations

Besides the problems with the dispensing stations, the distribution

of dispensing stations is also a problem. There are 31 stations in south

Delhi in comparison to 12 in north Delhi and 11 in central Delhi. East

and west Delhi have only nine stations each. While all the mother and

online stations are restricted to north and south Delhi, east Delhi has

only daughter stations and that too without boosters. All the nine stations

in west Delhi are daughter stations but only two with a booster.61 This

means that IGL must move fast to extend the pipeline to east and west

Delhi (see table 14: Weak links).

According to MOPNG, though there are 74 CNG stations in Delhi but only

16 online stations are catering to 75 per cent of the demand and that

is resulting in long queues.44 If this is true, it is obvious that this

is happening because better pressure is maintained at the online stations.62

Gas

allocation

MOPNG argues that production and supply of natural gas from the

ONGC wells are declining on account of the fact that these wells are more

than 15 years old. In this scenario, increasing the allocation of more

CNG to Delhi would mean decreasing the allocation of natural gas to industries,

power stations and fertiliser units which are being fed from the existing

gas pipeline. “This would have a serious impact on the economy of

the country” says the ministry.68 But the ministry is not concerned

about improving public health.

The ministry, therefore, does not want autos, taxis and cars to

get converted to CNG. Instead it wants them to continue to run on the

petrol (unleaded petrol with 1 per cent benzene) and diesel (with 500

ppm sulphur content) which are now available in Delhi. The ministry is

only prepared to assure gas supply for 12,000 buses. But this is only

the current busload in the city. The city is scheduled to grow from its

current population of 14 million to more than 22 million in 2021.69 How

will the gas needs of the future bus requirements be met? It is obvious

that the current allocation strategy has to change to take into account

public health.

The key issue here is prioritising allocation of natural gas. There is

much scope of allocating more natural gas to Delhi but MOPNG is not willing

to do that. Instead it is trying to raise the bogey of gas shortage.

Even as the transport sector is being starved of gas, piped gas is being

supplied to hotels and affluent households. It was first supplied to Kaka

Nagar, Bapa Nagar and Pandara Park in 1997 as a pilot project. Since then

it has been extended to Golf Links, Sunder Nagar and Sujan Singh Park.

More recently, gas supply has started in Nizamuddin (east and west), New

Friends Colony, Friends Colony, Maharani Bagh, Kalindi Colony, Sukhdev

Vihar, Sukhdev Vihar Pocket A & B, Ishwar Nagar and Zakir Bagh. In

addition, five-star hotels The Hyatt Regency, Hotel Taj Mahal, Hotel Oberoi,

Hotel Ambassador and Hotel Surya have switched over to natural gas for

commercial application like cooking, water heating, air conditioning,

space heating, and power generation.70

All these areas are high income areas which were earlier using LPG. Switching

from LPG to CNG will have almost no impact on pollution reduction. In

any case, there is no shortage of gas, it is a question of allocating

enough gas to meet the vehicular demand of Delhi.

Gas allocations are made by MOPNG on the recommendations of the Gas Linkage

Committee (GLC), which is an inter-ministerial committee with representatives

from the planning commission, and the Union ministries of finance, power,

chemicals and fertilisers and steel. The allocations are made based on

the requests received, taking into consideration the existing allocations

and the gas availability projections in different regions from time to

time.

In view of the importance of the fertiliser and power sectors in the national

economy, preference in allocations has been given to these sectors. As

and when shortage of gas is perceived in any region, an action plan for

the region is drawn up and approved by the GLC wherein fertiliser and

the power sectors are given priority. The departments of fertiliser and

power are consulted in this regard and the GLC, while approving the action

plan considers the bulk allocation for each of these sectors while leaving

the individual requirements of each unit to these departments within the

overall allocation for the sector. All gas-based units are required to

have dual fuel capability so as to use other fuels whenever availability

of gas is restricted.

The Planning Commission has set up a working group on petroleum and natural

gas for the Tenth Plan under the chairmanship of the secretary, MOPNG.

The working group has set up various subgroups including a subgroup on

demand of petroleum products and a subgroup on natural gas production,

availability and utilisation. The working group coordinates the functioning

of the various subgroups. This practice was also followed for the Ninth

Plan.

At present the gas allocation for consumers in Delhi is 3.07 MMSCMD (24.76

lakh kg per day) — 2.59 for power and 0.48 for other consumers. Out

of 0.48 MMSCMD (3.87 lakh kg per day) only 0.15 has been allocated for

transport and the remaining 0.33 MMSCMD (2.66 lakh kg per day) for households.

Though there is a proposal from IGL requesting GLC to allocate an additional

1 MMSCMD (8.06 lakh kg per day) of gas to Delhi, MOPNG has shown no intent

to approve the proposal.

IGL claims that the all their CNG stations are over-utilised and are working

at more than 100 per cent of their capacity. Gas dispensation capacity

is estimated on the basis of the 18 hours of operation per day. But as

of now they are operating their stations for almost 24 hours. But even

with this kind of utilisation, IGL is not able to meet the demand for

transport in July 2001. IGL’s dispensing capacity in July, 2001,

is 0.27 MMSCMD (2.22 lakh kg per day).

According to IGL, out of an allocation of 0.48 MMSCMD (3.87 lakh kg per

day) only 0.15 (1.21 lakh kg per day) MMSCMD has been allocated to the

transport sector. This means that IGL is already diverting 0.12 MMSCMD

(0.96 lakh kg per day) from the allocated gas to the domestic sector.

IGL can play around with supply as long as it is within 0.48 MMSCMD (3.87

lakh kg per day), according to its new managing director, A K Dey . Going

by IGL’s estimates, in September 2001, the total demand by the transport

sector will be 0.52 MMSCMD (4.2 lakh per day) and dispensing capacity

will remain around 0.54 MMSCMD (4.4 lakh kg per day). Both overshoot the

total allocation of 0.48 MMSCMD. Therefore, at least 0.06 MMSCMD (0.48

lakh kg per day) will have to be allocated from other sectors for Delhi

by September 2001.

According to MOPNG, Delhi will need a maximum of 2 MMSCMD of CNG (16.13

lakh kg per day) in June 2002. This means a further allocation of 1.52

MMSCMD of natural gas to the city is required. According to IGL’s

corrected estimates Delhi’s transport will need only about 1.4 MMSCMD

(11.33 lakh kg per day) by March 2002. This is just 4.1 per cent of the

capacity of the Hazira-Bijaipur-Jagdishpur (HBJ) pipeline with a capacity

of 33.4 MMSCMD (269.4 lakh kg per day). Even MOPNG’s inflated estimate

amounts to just 4.6 per cent of the capacity of HBJ pipeline. Thus there

is no reason why this demand cannot be met.

Intervention by the Supreme Court to increase gas allocation

The

Supreme Court has in the past intervened in the allocation of gas. The

allocation of gas for Mathura Refinery was made as per the directives

of the Supreme Court to supply clean fuel, that is, natural gas, to all

polluting industries in the Taj Trapezium Zone in order to save the ecology

and environment around the Taj Mahal. The polluting industries included

the Mathura Refinery and accordingly gas allocation of 1.4 MMSCMD (11.29

lakh kg per day) was made by the GLC to the Mathura Refinery. The pipeline

was laid and supply commenced in 1996.

There are precedents to show that gas allocation have been augmented to

meet higher demand from other sectors as well. Here are some instances:

In September 2000, allocation to Essar Oil Ltd was

increased by 0.7 MMSCMD (5.65 lakh kg per day) from 1.71 to 2.41 MMSCMD.

that is, an increase of 5.64 lakh kg per day. Similarly, Reliance Refineries

Limited got an increased allocation of 0.4 MMSCMD (3.22 lakh kg per day)

raising it from 0.49 to 0.89 MMSCMD.

In 1999, a new allocation of 0.85 MMSCMD (6.8 lakh

kg per day)was made to Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Limited (IPCL),

Dahej.

In July 1999, National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC),

Kawas was allocated 2.1 MMSCMD (16.94 lakh kg per day). NTPC was further

allowed NTPC to divert 1.5 MMSCMD(12.09 lakh kg per day) of the allocated

gas to their plant at Jhannore in 2001.

Allocation of 1.75 MMSCMD (14.11 lakh kg per day) of

gas was shifted from the proposed power plant at Bawana that did not come

up, to the proposed Pragati power plant of DVB in 2001. But Pragati power

plant is yet to see the light of the day.

Around 0.4 MMSCMD (3.22 lakh kg per day) of gas was

allocated to Gujarat Industries Power Corporation Limited (GIPCO), Vadodara,

by GAIL without any firm allocation.

Gujarat State Fertiliser Corporation (GSFC), Vadodara,

was supplied 0.8 MMSCMD (6.45 lakh kg per day) of gas to by GAIL against

an allocation of only 0.4 MMSCMD (3.22 lakh kg per day) by GLC.

DVB was given was given 1.2 MMSCMD (9.68 lakh kg per

day) of additional gas by GAIL against an allocation of 0.84 MMSCMD (6.77

lakh kg per day) by GLC.

GAIL supplied around 1.46 MMSCMD (11.77 lakh kg per

day) to different consumers against an allocation of 0.48 MMSCMD (3.87

lakh kg per day) by sanctioned by GLC.

The central minister of state for petroleum has written

a note to GAIL asking it to work for city gas distribution in the city

of Lucknow (the prime minister’s constituency) and Bareilly (constituency

of minister of state for petroleum). On the basis of this MOPNG has approved

a total allocation of 0.15 MMSCMD (1.20 lakh kg per day), of which allocation

for Lucknow is 0.1 MMSCMD (0.80 lakh kg per day) and 0.05 MMSCMD (0.40

lakh kg per day) for Bareilly.

All this extra allocation has been done after the Supreme Court orders

of July 28, 1998.

How can gas dry up if there are major expansion plans for gas supply in

the future?

The expanded infrastructure being planned for delivery of regasified LNG

to northern India is the expansion of the HBJ pipeline network from a

capacity of 33.4 MMSCMD (269.35 lakh kg per day) to over 60 MMSCMD (483.87

lakh kg per day). The first phase envisages 800 km pipeline network linking

Dahej LNG terminal with the HBJ system at Vemar in Gujarat and a parallel

42 inch pipeline to the existing HBJ pipeline from Vemar upto Vijaipur

to transport 30 MMSCMD (241.94 lakh kg per day) of additional gas to the

states of northern India. The investment in the first phase would be approximately

Rs. 2,968 crore. The second phase envisages additional compression facility

and expansion of the existing HBJ pipeline to Delhi and beyond to Haryana

and Punjab to meet the requirements of natural gas in these states. The

details of investment plans in the second phase are being worked out.

How can gas become scarce with such massive projects in advanced stages

of planning?