"Agricultural

issues need to be approached with a two-track strategy"

Interview with Biswajit Dhar, Head, Centre for WTO studies, Indian Institute of

Foreign Trade.

CP: Why has agriculture been touted as one

of the most significant issues for developing countries in the Doha Round of negotiations?

BD: Agriculture is the most significant sector for Developing Countries

(DCs) considering the large population that is dependent on this sector. Lets look at

India's case. Even after going through the process of industrialization, the population of

workforce dependent on this sector still remains at about two-thirds of the total. And

while the share is decreasing, a fairly large number still prevails for other DCs that are

in India's category; this is why the agreement on agriculture and particularly its review

has become so important for the DCs.

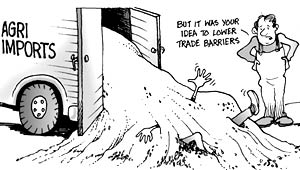

This is so because of the inherent problems in the agreement. I will concentrate on the

major problems of the agreement. The first is that the basic structure of the agreement is

tilted in favour of developed countries. DCs are crippled due to an absence of a rule on

special and differential treatment. And, the second problem is the way the agreement has

been implemented. It leaves a lot to be desired. At the end of the Uruguay Round (UR), DCs

expected considerable reduction in subsidies in developed countries. Contrary to

expectations, developed countries have increased subsidies, thereby taking advantage of

prevalent imbalances. Consequently, DCs agenda was very clear. They identified the

agricultural sector to provide food security and livelihood for a majority of the

population. Certain countries like India were also thinking of dividing this sector into

tradable and non-tradable commodities. This would help them realize the sector's potential

by giving them better market access in larger markets. The market access problems were

however, getting into a jam because of the high level of subsidies in developed countries;

and also, because of high tariffs on certain products that are of export interest to

developing countries. In the negotiations, therefore, DCs like India had both a defensive

and an offensive interest. Under the UR negotiating framework, DCs were rewarded

substantial compensations in agriculture, for greater market access in their countries

through removal of QRs on imports and a slight relaxation on the TRIPS issue.

CP: Could you put some numbers to these arguments?

BD: The number gains were in a broad aggregative sense. The World Bank, the OECD

and others threw around different models. In one of the projections, the OECD-WB model

talked about a gain in income to the amount of around US $213 billion for the world as a

whole. The interesting part about this was that only one-thirds would accrue to the DCs,

among which India, China and Korea had the bulk of the share. It was predicted that LDCs

won't gain much; but India stood to gain, which was something to look forward to.

Intuitively, once market distortions like subsidies and tariffs get reduced, low cost

producers like India stand to gain due to an appreciation in prices. Once these

distortions were removed, the market would provide appropriate signals to farmers, who

could then adjust their production in response to these signals. Farmers in DCs had an

advantage in this case because of their cheap technology and low cost of production. When

international prices rise, it reduces the risk of cheap imports too, thereby widening the

domestic market further. Ideally, once the levels of protection are lowered, we gain

better market access to both domestic and foreign markets.

CP: Are there any other factors that hinder India's agricultural progress?

BD: One must not forget that the WTO is not the sole determinant of our

agricultural fortunes. There is considerably more that needs to be done domestically. In

my view, we need to approach this issue with a two-track strategy. So, while we attempt to

create a space for our agricultural goods internationally, it needs to be ensured that the

domestic market does not get affected.

What has happened though is that while trying to negotiate on a global scale, we have

ignored the problems on the domestic front. It is a known fact that the gains in

productivity are gradually slackening, since the end of the green revolution. There is

also the problem of very high cost inputs, which is jacking up the cost of production.

This is a major problem currently. Due to the ineffective implementation of the agreement

on agriculture the prices of commodities are coming down, which lands us in a double

whammy; On the one hand, the cost of production is rising, while on the other, the prices

are falling. In this respect, there is a complete reversal to the ideal scenario that I

referred to earlier. High protection is essential to protect our farmers from cheaper

imports. A similar situation exists in other DCs, except for a small number of

agricultural exporters like Malaysia, and some Latin American countries. Except those

countries, which have a sizeable interest in the international markets, most other DCs

have a subsistence agricultural sector; and it is these countries that are now looking

down the barrel.

CP: There are broadly two-aspects to the agricultural negotiations - one are the

trade concerns and the other are the non-trade concerns. Which is the most crucial for

DCs?

BD: Both concerns. This is exactly what I was talking about when I said that we

have both an offensive and a defensive interest. Our defensive interests, like food

security and livelihood are encapsulated within the non-trade concerns. Most farming in

our country is for subsistence. These farmers participate in the market only at the

margin, and hence are most vulnerable to cheap imports. This will erode their little

marketable surplus, thereby reducing their capacity to meet their non-food needs.

Trade concerns obviously refer to market access. The crosscutting issues within these are

tariffs and subsidies. High tariffs and subsidies create problems for both trade prospects

and non-trade concerns.

CP: Most countries have put forward their proposals on agriculture. If you had to

identify certain contentious issues on which these countries are willing to stick their

neck out, what would they be?

BD: From a DCs perspective, these issues would certainly entail a reduction in

subsidies by developed countries. It may seem paradoxical that why should developing

countries employ high tariffs once subsidies granted by developed countries get reduced.

In my opinion, this contradiction gets resolved once we consider the current market

scenario, where any reduction in subsides is meaningless in terms of improving the

discipline in the market.

Stuart Harbinson, the Chairman of the WTO on Agriculture, in his paper has tried to give a

broad framework of the possible changes that could take place in the existing Agreement on

Agriculture (AoA). In his proposals, he hasn't advocated the case of reduction of domestic

support strongly. This is because both the EU and US are heavily committed to giving high

subsidies to the farming community. The US legalized a Farm Act last year, according to

which domestic support between 2002 and 2011 would inflate by US $180 billion. The EU has

a larger share for subsidies than the US; and once the Eastern European countries join in,

there will certainly be an enormous rise in the amount. Undeniably, there will be a huge

increase in subsidies; the issue is by how much. Given such a scenario, DCs demand for

higher tariffs are legitimate.

CP: You mean DCs should increase tariffs for greater protection?

BD: No! Not increase, but retain tariffs at previous levels or agree to minimum

cuts. There have been various kinds of formulas, which have been tried out but one is

unsure about their prospects. India has been amongst the most vocal DCs. It will be very

difficult for her to settle for substantial cuts in tariffs. At the moment, we are intent

on keeping our tariffs at a reasonably high level, while we diligently attempt to

discipline the subsidies, fully cognizant that it may be futile.

CP: I return to my previous question. For which issues are various countries

willing to stick their neck out for?

BD: The US is the unofficial leader of the Cairns Group, which is essentially

demanding better market access in developed countries. The US, in particular, has very

aggressively campaigned for a reduction in tariffs in DCs, arguing that DCs comprise of

the largest and the most protected agricultural markets in the world. Tariffs in developed

countries are in any case low; so they don't have much to offer. This is the US position.

The Cairns group, however, doesn't go that far because its majority comprises of DCs. The

Cairns group, while demanding better market access, are concerning themselves chiefly with

a reduction in subsidies. The US is talking about reduction of subsidies, which are

trade-distorting in character. There have three types of subsidies that have been

identified, of which Green Box is non trade-distorting. The US has been supporting the

group only through its Green Box measures.

The EU, on the other hand, has no intention of reforming the agricultural system. Neither

do they want to reduce tariffs substantially, nor reform their domestic support; their

only demands are controls on export subsidies, export credit and food aid. The US

currently grants quantum support through measures like export credit and food aid.

Comparably, the EU agenda is more transparent. It has no intentions of reforming the

agricultural sector, and therefore will go into the negotiations with a few points in

hand. The US, on the other hand, is trying to project that it has a major agenda for

reforming agriculture; but, in effect, it will do nothing. Superficially, they may try to

clamp down on trade-distorting support, but, unless they repeal the Farm Act of 2002, we

can expect quantum increase in domestic support in the next few years.

CP: Doesn't the EU also want to retain the Green Box measures?

BD: True. The EU has very little ambitions in this sector, and this is exactly what

we may see in their proposals. There will be no hypocrisy in their proposals. While the US

may strongly voice their support for major reforms, yet will not initiate any action on

the same count.

CP: In that case, where can we expect reform then?

BD: In my opinion, we may not see any reform if the present trend continues. This

impasse will continue unless somebody breaks this rule of the jungle.

CP: What are the prospects for agriculture then from the current round?

BD: My apprehensions are that there could be some deal between the US and the EU.

At the moment, the EU would appear to be a natural ally to most developing countries. This

is so because disciplining of subsidies is not in the control of DCs either. And, unless

subsidies are disciplined, tariffs cannot be brought down. The DCs agenda on this is very

clear; until subsidies are lowered, it is impossible to expect any market

discipline.

CP: Do you foresee developing countries arguing for increase in their current

levels of tariff support, if subsidies do not get reduced substantially?

BD: This was one of the suggestions that if the impact of subsidies does not get

reduced then, there would have to be a compensation mechanism, which will work through the

tariffs. Earlier, very few developing countries had the right to use special safeguards.

Now, they are being used by DCs in a more general manner. However, there are technical

details like the trigger price and the tariff level that still need to discussed more

comprehensively.

Even though safeguards are only temporary measures, one could argue that they are

effective in combating perceived threats from cheap imports. The length of time for which

they can be used becomes immaterial, once they provide the option for recourse.

DCs are also aware of this tricky situation. Increasing tariffs will involve considerable

costs for them. In the past, when we increased our tariffs on certain commodities, other

tariffs had to be correspondingly reduced. That is the way the WTO system functions. For

every bit of protection or a safeguard mechanism, there will be some compensation

elsewhere. In terms of strategy, it is not really a bad idea that we are not going

overboard on the issue of increasing tariffs. It will not be granted to us in the first

instance, and then it may be difficult for us to argue for it later. It would be better

for us to have certain measures in place where we can protect our own markets.

CP: How do you think India should approach these agricultural negotiations?

BD: I think the issues we have raised upfront are very valid. We raised the issue

of non-trade concerns, including both food security and livelihood. Our basic contention

was that agricultural policy making had to have a larger perspective; it cannot be purely

trade-based. Our aim is to make the system more flexible, lest the farming community back

home refuses it. I think that the negotiators are aware of the situation among the

affected groups. There cannot be a repetition of the imbroglio that resulted due to lack

of understanding during the UR negotiations. We will therefore, not accept any agreement

that is lop-sided or does not address some of our core issues seriously.

In the past, several analysts have argued that India's real advantage lies in exports.

Since the UR negotiations have assured us that international markets will open up, we need

to shelve our anti-export sentiment, and try to realize the sector's export potential.

There persist two problems in this export-orientation thesis. The first is if we go

overboard trying to produce commercial crops, we may effectively ruin our cropping pattern

by substituting non-food crops for food crops. Developed communities like the EU and the

US have recently become major producers of food crops like rice, wheat, maize etc. DCs

enjoy a comparative advantage in producing cash crops. If the market diktat were to be

followed, then it could be dangerous for us because it may make us dependant on them for

food. This could destroy our balance of payments situation substantially. DCs have been

warned of such pernicious effects by multilateral organizations like the Food and

Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Summit initiatives. Secondly, for

export-oriented growth, we will need to commodify the agriculture sector, since access to

international markets will not be easy to gain. The EU and the US have made use of an

increasing number of non-trade barriers to protect their sectors. The quality of our

products will not be able to survive international competition at the moment. So, unless

we fundamentally reform our domestic production system, it is not going to be easy to get

market access there. This is why I emphasize on the need to modernize domestic production

techniques. The kind of products that we sell in our markets is not going to be accepted

anywhere. This has weakened the argument for making agriculture an export-oriented

sector.

CP: Are we looking to address these non-tariff barriers, like food safety standards

and environmental standards?

BD: We are. But, it is not a part of the agricultural negotiations. It is a part of

the negotiations on SPS and TBT. They don't get linked here. That is another problem area.

All the market access issues do not get addressed in the agricultural negotiations. We

don't use TBT or SPS to the extent that developed countries do. We would have liked to

raise this issue as a larger market access problem; but we can't do it because SPS is not

a part of the AoA.

CP: Aren't those bodies looking at the issue of standards for agricultural

products?

BD: They are. SPS is entirely concentrated on agricultural products. TBT is also

being used. Yet, I am sure in both these agreements, countries are free to use their own

national standards. Consequently, there is derogation from national treatment, which is

provided for in both these agreements. The slower these agreements move, the better it is

for developed countries that use these discriminatory practices.

CP: You have made the case for the liberalization of agriculture benefiting

developing countries. And in liberalization, the international prices are going to rise.

Now, there are quite a few DCs, which are actually net importers and are likely to be

affected by the increase in prices. How is that being addressed?

BD: There is a separate decision on net food importing DCs and LDCs. A part of that

decision was that these countries will be provided technical assistance and

capacity-building measures to strengthen their domestic agricultural sector, apart from

concessional aid for food imports to meet their current food needs. Again, this is a part

of the larger objective of ensuring food security. These decisions will provide a

facilitating environment to ensure that the countries can depend on their own domestic

production to be self-sufficient. Green Revolution in India was a set of techniques that

were aimed at these very objectives. Unfortunately, the process of Globalization and trade

liberalization has put the clock back. And, as I have already mentioned that the FAO and

the World Food Summit have already taken initiates to deal with such problems.

CP: Is there a strong linkage between high protection on geographical indicators

and the agricultural negotiations?

BD: The EU has made that linkage but I don't think that it will be accepted by

anyone. What could be important is the other part of the non-trade concerns, which the EU

has raised in the form of multifunctionality. These comprise animal welfare payments,

environmental protection etc. This will raise the subsidies bill of DCs

considerably.

CP: In the final analysis how do you see things progressing from now because there

is a missed deadline on modalities? What is happening currently and how is it likely to

progress?

BD: At this moment, it is very unclear how things will progress. We can only hope

that nothing disturbs the Cancun process. I mean if the EU and the US strike a deal, then

it could be a fait accompli for the DCs. Everyone is aware that the making or breaking of

Cancun depends on agriculture. If the EU and the US submit a joint proposal, which is

disagreeable to the DCs, then we would get the blame for wrecking the multilateral system;

If they don't come up with a solution, then we are no better than we were before. At this

point, there seems to be no resolution to break this deadlock; we will have to wait for

the Cancun negotiations to start before making any further predictions.

CP: On the one hand, we are asking them to come to an agreement and on the other

hand if they do come to an agreement, that may not be acceptable to us.

BD: That is the crux of the problem. Nobody wants to take the blame for missing the

deadline. All claim that there was a common consensus among DCs, and the progress of

negotiations was impeded because the EU and the US could arrive at no compromise. In

retrospect, the UR negotiations were clinched because the EU and the US signed the

Blairhouse Accord. The Blairhouse Accord had disastrous consequences for the DCs.

CP: Shouldn't we be more proactive here and come out with our own proposals?

BD: Sure, at both the government and the civil society level. I think a large part

of the interventions in the WTO have originated from civil society concerns. Civil society

has a considerable role to play and unfortunately for India, civil society hasn't really

taken up the issue as much. This really surprises me. The kind of interest that civil

society groups had during the UR negotiations or immediately thereafter hasn't been

repeated since. I can safely generalize this for multilateral processes in particular. The

kind of co-ordination expected from civil society groups in India hasn't been witnessed

yet. It is surprising that western groups have raised most issues of concerns to

developing countries.

CP: Is that because the DCs civil society is more inward-oriented and they are not

well aware of the international issues?

BD: Certainly, that is one of the problems. But, even the problems that we raise,

we do not articulate them well enough. For instance, even if we concentrate on issues like

agriculture or environment, we should be documenting all problems for different regions or

sections that are affected. They should have in hand case studies, anecdotes and similar

material to mount a strong case. We need to be more proactive on issues of concern to our

country.

For agriculture, we can't depend on government statistics. They do not provide us with

comprehensive statistics. This is where the civil society groups can contribute most. They

need to carry out ground research, prepare strong cases and keep a check on government

activities. It would be a gargantuan task to identify countries with whom we share a

common cause; but the more important concern at this point is to get our own act in place.

CP: Finally, how would you react to the proposal that Harbinson has put forward?

BD: It is very low on ambitions, at least on the issues that concern us, like the

subsidies issue.

CP: And what about the other non-trade concerns?

BD: This is still in the melting pot. We have to wait and see how much protection

do these concerns get. The list of special products that we can give higher protection to

is yet to be decided. All these issues are still on the negotiating table and we might

benefit if some of the proposals on domestic support are taken on board. But, I think what

will happen is that the Harbinson's text will go through, which will mean that our tariffs

will come down on a large number of products. We will not be able to identify the

strategic products. The list of strategic products may vary over a period of time. This

dynamic situation has been created due to subsidies. Unless we solve this basic problem,

any amount of tariff reduction is going to be totally useless. Our focus should be to

attack subsidies in developed countries.

|