| |

What goes down must

come up

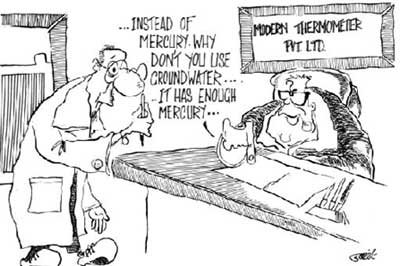

It is a crime.

Numerous factories deliberately inject untreated effluents

directly into the ground, contaminating underground aquifers.

Samples of groundwater were collected from eight places in

three states and tested for concentrations of some known pollutants.

All samples had high levels of the heavy metal mercury, which

caused the Minamata disaster in Japan in the 1950s. One sample

had more than 268 times the mercury than is considered safe.

Groundwater in the industrial areas of India is unfit even

for agriculture.

In february 1999, a Delhi newspaper reported that a tubewell

sunk to a depth of about 200 feet (61 metres) by Suruchi Dyeing

Udyog, a factory south of the G T Road in Ghaziabad, Uttar

Pradesh, was yielding yellow-coloured water. Arun Agarwal,

the factory’s owner, was quoted in the report as saying:

“Initially, we thought it was surface impurities that

came up with the water. But then we found it was the groundwater

itself. It is pure poison.” The Central Ground Water

Authority (CGWA) found para-nitrophenol, an organic compound,

in the water in a concentration of 0.54 milligrammes per litre

(mg/l). The permissible limit of the compound is 0.001 mg/l.

Obviously, some factory in the area that was pumping untreated

effluent into the groundwater.

Earlier, in January 1994, the Central Pollution Control Board

(CPCB), Delhi, had undertaken the first major groundwater

quality monitoring exercise. The report published in December

1995 identified 22 places in 16 states of India as ‘critical’

sites of groundwater pollution. cpcb found industrial effluents

to be the primary reason for groundwater pollution.

Considering that 80 per cent of the country’s drinking

water needs are met by groundwater, Down To Earth sent

its reporters to some areas where groundwater contamination

has been reported. They brought back samples from eight places

in three states: Haryana, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. The

samples were analysed at the Facility for Ecological and Analytical

Testing (FEAT) of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT),

Kanpur. The results were shocking. There were traces of heavy

metals like iron and zinc in all the samples, cadmium in five

samples and lead in three. But all the samples had one striking

similarity: the levels of mercury were dangerously high.

Mercury is implicated in a range of health problems, including

Minamata disease (characterised by impairment of brain functions),

neurological disorders, retardation of growth in children,

abortion, disruption of the endocrine system (which controls

hormone levels in the blood stream) and weakening of the immune

system. “High levels of mercury in drinking water can

severely impair the nervous system, causing neuropathy. Moreover,

it affects lever and kidney functions,” says S K Wangnoo,

senior consultant and endocrinologist at the Apollo hospital,

New Delhi.

The concentration of mercury in the sample taken from a tubewell

near an industrial area in Panipat was 0.2683 mg/l, more than

268 times the permissible limit of 0.001 milligrammes per

litre (mg/l) set by the World Health Organisation for drinking

water. The chemical oxygen demand (cod, which is the amount

of oxygen required by chemicals in the water to oxidise

and stabilise themselves) of the water was 360 mg/l. The maximum

permissible cod level even for industrial effluents is 250

mg/l. The groundwater is as bad or worse than untreated industrial

effluents.

Wellwater from Lali village, about 15 km from Vatva in Gujarat,

showed 0.211 mg/l of mercury, again more than 200 times the

permissible limit. And the residents of the village drink

this water besides using it for irrigation. The COD level

of the sample taken from a borewell in Chiri village of Vapi,

Gujarat was 263 mg/l, indicating the overbearing presence

of chemicals. Among other sources, mercury can enter the environment

from units dealing with smelting, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers,

chemicals and petrochemicals.

“Of all the commonly occurring metal pollutants, mercury

is the most toxic,” writes Padma S Vankar of feat, Kanpur.

“The indiscriminate discharge of mercury along with industrial

pollutants... may result into significant build-up of the

metal in the aquatic environment,” she points out. “No

guideline exists for mercury in irrigation water. A nationwide

approach to solve mercury pollution needs to be taken up.

A balanced strategy which integrates end-of-pipe control technologies

with material substitution and separation, design-for-environment,

and fundamental changes in approach,” she notes. She

suggests that more tests should be conducted on groundwater

to find out the extent of pollution, especially with regard

to cyanide, arsenic and banned amines.

In all the places visited by the Down To Earth reporters,

residents of the surrounding areas were unaware of the danger

in groundwater, though they could see that something was wrong.

As for the government authorities, the pollution control boards

are either unwilling to deal with the offenders or are simply

ineffective at implementing the anti-pollution laws. Then

there are the all-too-familiar complaints of connivance with

rogue industry.

On December 10, 1996, the Supreme Court directed the Union

ministry of environment and forests (MEF) to empower the Central

Ground Water Board (CGWB) under the ministry of water resources

to initiate penal action under the Environment Protection

Act, 1986, against overexploitation of groundwater. This led

to the creation of cgwa. But in the past three years, cgwa

has invited a lot of criticism. It is quite clear from the

Down To Earth case studies that pollution control authorities

are not capable of dealing with the groundwater crisis.

The only solution is to involve the local people and civil

society in checking further pollution of our groundwater as

they are the most important stakeholders of the country’s

natural resources and are the worst affected by pollution.

This is all the more important in light of the fact that once

polluted, cleaning up groundwater is next to impossible. It

is a tough task for our bureaucratic establishment, which

completely lacks transparency. The case studies are presented

here with the hope that policymakers and the general public

alike awaken to the crisis

Disasters in the

making?

Groundwater contamination in India

is verging on disastrous proportions, especially with regard

to mercury

Down To Earth reporters met the pollution control authorities

in some industrial areas of the country, spoke to the local

people about the effects of pollution and met representatives

of the civil society to gauge the extent of the problem on the

socio-economic level. They also got in touch with industrialists,

but this exercise was largely fruitless as industry is very

wary of coming out in the open to discuss its problems, all

the while proceeding with irresponsible practices. Some case

studies are presented here.

|

Paks Trade, a Patancheru-based company,

was apprehended for pumping arsenic-laced effluent into

the ground through borewells

|

Patancheru:

Andhra Pradesh

The DTE/IIT test conducted on a water sample from a handpump

in Pocharam village of Patancheru Industrial Area (PIA) in Medak

district of Andhra Pradesh showed that the level of mercury

was 115 times the permissible limit. A study conducted by National

Geophysical Research Institute, (NGRI), Hyderabad, found that

arsenic levels in villages in and around PIA are as high as

700 parts per billion (PPB, as against the permissible 10 PPB

recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The study

also found that the manganese level in the groundwater sample

from Bandalguda area was 15 times the permissible limit, whereas

the concentration of nickel was 4-20 times the permissible limit.

“We caught Paks Trade, a Patancheru-based company, for

pumping arsenic-laced effluents into borewells,” says Tishya

Chatterjee, member secretary, AP Pollution Control Board (APPCB).

“We have also found high levels of cadmium in the groundwater

samples in AP’s industrial areas,” he adds. It is

common knowledge in Patancheru that most of the 400 industrial

units cannot treat effluents properly and that they dump them

in the open or inject them directly into the ground. Chatterjee

points out that there are several other industrial units that

also indulge in such practices, but there are no clear-cut rules

to stop such polluters (see box: Killers

at large).

ITW Signode, another Patancheru-based company, was discharging

toxic, strontium-laced effluents into a nearby drain. An NGRI

study found high levels of strontium in the groundwater. “We

located this industry and closed it,” says Chatterjee.”

A study by the groundwater department of the state government

confirms that the pollution level is very high and has endangered

human lives, animals and agricultural activity.

The NGRI study says that most of the industrial units deal

with pharmaceuticals, paints, pigments, metal treatment and

steel rolling. They use inorganic and organic chemicals as

raw materials, which are reflected in appreciable amounts

in the effluents. Units in Patancheru and Bollaram discharge

about five million litres of effluents everyday. A major part

of the untreated effluents ultimately goes into nearby tanks

and streams. A certain part is clandestinely disposed of in

dry borewells.

K Subrahmanyam, scientist at NGRI, says the total dissolved

solid (TDS) levels in groundwater have been reported to be

as high as 2,310 mg/l in Patancheru borewells. The permissible

limit for TDS is 500 mg/l, and the TDS concentration in the

natural groundwater (from aquifers that have not been affected

by human activity) in the area is 300-350 mg/l. The characteristics

of these effluents are alarming. Independent studies show

that various parameters, such as COD levels, are exceeding

the prescribed limits. “The common effluent treatment

plants (CETPs) at Patancheru and Bollaram do not work up to

the required efficiency. So, effluents with TDS levels of

more than 20,000 mg/l are only treated up to 8,000-9,000 mg/l

levels. And many a time, these CETPs discharge the effluents

in the nearby streams without treatment,” Chatterjee

reveals.

The state government’s assessment observes that between

1984 and 1989, total land affected due to industrial effluents

in terms of crop loss is 560 hectares in Patancheru and Bollaram.

A 1991 survey by National Environmental Engineering Research

Institute (NEERI), Nagpur, estimated the affected land area

at 695 hectares belonging to 581 farmers. The survey revealed

some unusual signs. People of the area complained of a plethora

of diseases such as epilepsy, skin and throat problems, respiratory

diseases, cancer and paraplegia (paralysis of both the legs),

while pregnant women are giving birth to still-born children,

says the NEERI expert.

N Ramdas Goud, 46, of Pocharam, says: “The colour of

the groundwater became yellow 7-8 years ago. Our crops started

getting damaged whenever we used water from the borewell.

Cattle have died in the past after drinking the effluent water

from a stream flowing near the village. This is why we launched

an agitation against pollution and took the matter to the

Supreme Court (SC).” Goud says that in its interim order,

SC directed supply of clean drinking water and compensation

to affected farmers (see box: Tankers from hell). “But,

even today, many industrial units comply neither with judicial

directives nor with administrative orders in establishing

ETPs,” says K Purushotham Reddy, who heads the department

of political science at the Osmania University, Hyderabad.

He is the president of Citizens Against Pollution, an environmental

activists’ group.

|

An employee at a dyeing unit in Panipat

says the factory has built a toilet above the mouth

of a borewell to inject effluent into the

|

Panipat:

Haryana

When IIT, Kanpur, tested a sample of groundwater from Panipat,

the mercury level was found to be 268 times the permissible

limit. The presence of chemicals was found to be more than what

is permitted for industrial effluents. “Groundwater in

Panipat stinks, sours milk, corrodes containers and can take

life instead of giving it,” says a housewife living in

the Tehsil Camp area of the town, describing the water from

her tubewell. There are numerous dyeing industries in the surrounding

areas. “Chemical effluents pumped into a borewell by some

of these industrial units mixes with our tubewell water,”

explains Janak Singh, her husband. Although the family stopped

drinking the water from the tubewell some four years ago after

complaints of stomach disorders, the Singhs still use the water

for washing and bathing.

However, J C Yadav, administrator of the Haryana Pollution Control

Board (HPCB), Chandigarh, says the practice has been discontinued:

“Earlier, say a decade ago, it was widespread. And that

industries were doing it was public knowledge.” But it

is common knowledge in Panipat that the industrial units involved

in dyeing and dye-related operations pump effluents into the

ground.

In 1994, R H Siddique of the environment study project at the

Aligarh Muslim University, on behalf of dte, tested effluents

being dumped into the aquifer. According to his findings, effluents

with cod levels as high as 2,400 mg/l were pumped into the aquifer.

M C Gupta, director of the state’s groundwater directorate,

says the effluents already pumped in would definitely show up

in the quality of the water. In fact, it has already shown up.

M Mehta, regional director, CGWB, Chandigarh, says: “Water

samples we collected are coloured. It implies that the quality

is no more fit for drinking.” CGWB is now testing the samples

and one of its scientists says, “Preliminary studies show

that the water is not even fit for agriculture, forget about

drinking purposes.” But Yadav defends his point, saying,

“Though the injection of effluents into the aquifer has

stopped, the groundwater remains vulnerable to the highly toxic

effluents that run through a open channel through the city.

This toxic water can percolate and pollute the groundwater.”

Till 1994 it was common practice among industrial units to pump

effluents into the ground. But in 1994, HPCB started enforcing

pollution control measures. “But nothing has changed. These

industrial units still pump in effluents, though clandestinely,”

says Anil Kumar, a laboratory assistant in a local college,

adding that the groundwater of Panipat was clear and fit for

drinking a decade ago. His handpump, hardly half-a-kilometre

away from a cluster of dyeing units, gives pink- and yellow-coloured

water.

The field visit of the Down To Earth reporter to some

industrial areas belies the claim that factories have stopped

injecting effluents into underground aquifers. Dyeing units

are pumping their effluents into the aquifers through bore wells

in Tehsil Camp, Jattal Road and the Sector 29 industrial areas

even today. An employee of a dyeing unit in Tehsil Camp points

out, “This unit has been doing it for 15 years. Earlier,

it was public knowledge. But now it does the same thing in a

rather clever manner. Three years ago the owner of the unit

built a toilet just above the borewell. In place of the commode,

you have the mouth of the borewell. Nobody would doubt it.”

It is not easy to believe that hpcb does not know this.

Local residents confirm that the designs of industrial premises

have been altered to cover up the nefarious practice. More factories

have built huge concrete walls around the premises and entry

is restricted. “Even for us it is very difficult to enter

the factory. We know they have clandestine mechanisms to pump

in the effluents,” says a scientific officer of hpcb in

Chandigarh.

|

“Ludhiana city’s groundwater

is just short of poison”

—

M Mehta, regional director, Central Ground Water Board,

|

Ludhiana:

Punjab

|

Before making any mention of the status of groundwater in

this industrial nerve centre known as ‘Manchester of

India’, it is important to remember that groundwater

is Ludhiana’s only source of water. The largest city

in Punjab with about one million people, its annual drinking

water requirement is 44 million cubic metres (cum), against

an estimated annual replenishable groundwater of 23 million

cum. So, to meet the demand-supply balance, deeper aquifers

are being accessed and overexploitation is rampant. In order

to provide assured water supply, the municipal corporation

is exploiting groundwater resources through 80 extraction

points. Besides most residents and industrial units also extract

groundwater. And no prizes for guessing the status of the

groundwater.

“Ludhiana city’s groundwater is just short of poison,”

says M Mehta, regional director, cgwb, Chandigarh. The culprits

are 1,311 thriving industrial units that are engaged in producing

cycles and textiles, among other things, and include foundries.

According to a CGWB report, the units are discharging about

50,000 cum of industrial effluents — mostly of toxic

contents — each day into the Budha Nala, a stream that

recharges the groundwater of the city. The stream travels

through the city to the point of its confluence with the Satluj

river 20 km downstream.

The pollution of groundwater reached such a proportion in

1993 that the Punjab Pollution Control Board (PPCB) wrote

to the state government asking for signboards to be put around

shallow tube wells stating ‘water unfit for drinking’.

However, six years down the line, you can go round the city

and not find a single signboard. Rather, people are still

using water from shallow aquifers. “The first aquifer

is already polluted. If not checked it would percolate down

to the deeper aquifers,” says R Nath, who was professor

of biochemistry at Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences,

Chandigarh, before he retired.

To identify the industrial units pumping effluents directly

into aquifers, the ppcb put a series of advertisements in

newspaper declaring a cash award to informants. “Not

a single person informed us about it though there have been

reports that some industries are doing it for years,”

says D K Dua, member secretary, ppcb, Patiala. Yet, Dua insists,

that pollution is reducing: “The pollution level in the

groundwater is declining, as our studies show.”

But studies by CPCB, and more recently by CGWB, contradict

Dua’s statement. CGWB’s report on Ludhiana’s

groundwater status affirms that many industrial units are

deliberately pumping effluents into the aquifers. The groundwater

is a cocktail of heavy metals, cyanide, alkaline content and

pesticides. The groundwater board found that levels of heavy

metals such as cadmium, cyanide, lead and chromium were all

above permissible limits in the shallow aquifers, while traces

of arsenic were within the permissible limit. Small quantities

of these heavy metals were also traced in the deeper aquifers.

|

“It has been a common practice

in Gujarat to pump effluents into the ground”

—

A Gujarat-based environmental activist

|

|

“During heavy rains, production

levels increase greatly in Gujarat as effluent is dumped

to be washed away with the water”

|

Gujarat:

industrial estates

VATVA: “It has been a

common practice in Gujarat to pump effluents into the ground

directly through borewells, a deliberate attempt to kill people,”

says Rohit Prajapati, an activist of the Paryavaran Suraksha

Samiti (PSS), a network of activists working in Bharuch, Vadodara,

Surat and Valsad districts. Groundwater within a range of 30-35

km of the Vatva Industrial Estate (VIE) in Ahmedabad district

have been contaminated. In the absence of suitable modes of

disposal, indiscriminate discharge of effluents has caused serious

pollution of groundwater.

The DTE/IIT test on a sample of groundwater taken from Lali

village, about 15 km from Vatva, showed that the mercury level

was 211 times the permissible limit. The concentration of the

heavy metal in a sample from Machua village near Vatva was more

than 70 times the permissible limit. Residents of Lali are forced

to drink contaminated water and use it for irrigation. The village

is adjacent to a seasonal river Khari, which comes through Vatva

and has been reduced to a sewer and only carries industrial

effluent. Other villages along the bank of the stream face similar

problems. People suspect leaching of effluents into the groundwater

for the contamination.

“The groundwater has become so polluted that we get red-coloured

water even at a depth of 400 feet (122 metres). Crop production

has been gradually reduced to half of what we used to get 30

years ago. Earlier, we used to produce around 1,200 kg of paddy

in one bigha. But now, we can grow only 600-800 kg in the same

land,” says Kantibhai N Patel, 75, a farmer from Lali.

“All our attempts to report the groundwater pollution to

the authorities have been in vain,” says K K Patel, 68,

another farmer from Lali. “Recently, two young people lost

their lives after entering my well. It shows how polluted the

groundwater is in the area,” he adds.

For years, about 1,500 industrial units in Vatva, manufacturing

chemicals such as H-acid, dyes, sulphonic acid and vinyl sulphones,

have dumped chemical wastes on their premises or by the roadside.

“We cannot use the groundwater even for washing as it causes

skin problems. We are completely at the mercy of the local industry

for drinking water,” says Kalosinh Bihala, 29, of Machu

Nagar in Vatva.

ANKLESHWAR: The DTE/IIT

test conducted on water from a well in Sarangpur village in

Ankleshwar Industrial Estate (AIE), Bharuch district, revealed

that the mercury level was more than 100 times the permissible

limit. Water from a borewell in Bapunagar village near Ankleshwar

had 170 times more mercury than is considered safe. The 1,605-hectare

aie has about 1,500 industrial units, which manufacture dyes,

paints and pigments, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and pesticides,

among other things. Effluents from these units have severely

contaminated the underground aquifers.

When the Down To Earth reporter visited a well in Sarangpur

village, the colour of the water from a tubewell was red.

“We are using this water for the past six years to cultivate

wheat and cotton crops in around 2.5 hectares of land. We

do not have any option,” says P T Patel, the owner of

the well. In Bapunagar village, water from a tubewell is yellow

in colour. This borewell draws water from 150 feet (46 metres).

“In the past seven years, the water has become so polluted

that we cannot even wash our clothes with it,” says Samar

B Yadav, who owns the borewell. Gujarat Pollution Control

Board (GPCB) officials have taken the water samples many times

but have not taken any action so far, he complains. Villagers

say GPCB officials have acknowledged the extreme toxicity

of groundwater. “But we think they are as helpless as

we are,” he adds. “The state and central governments

are silently watching our pitiable conditions,” says

Ziya Pathan, 39, of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties

(PUCL), a non-governmental organisation (NGO).

PSS has found that of the 65 handpumps and borewells in the

slums of Shantinagar, Bapunagar and Miranagar on the fringes

of aie, 55 yield coloured water. The colour varies from red

to yellow to brown. As most borewells have been closed due

to toxicity, there is little water for irrigation. Farmers

in villages such as Dhanturia, Pungaman and Amboli use effluents

for irrigation. “My entire crop was destroyed when I

used water from the Piraman nala (a nearby stream that carries

untreated effluents from aie to the Narmada river),”

says J M Patel, 75, a farmer from Dhanturia, which is about

20 km away from gidc, Ankleshwar. He lost Rs 2,00,000 in the

process.

VAPI: The situation in

Vapi Industrial Estate (VIE) in Valsad district is no better

than other industrial estates of Gujarat. More than 1,900

industrial units have jeopardised the groundwater resources

of the area mainly by indiscriminate disposal of hazardous

wastes and effluents. A fair share of the effluents is also

being dumped into the ground. The DTE/IIT test conducted on

a sample of water from a borewell in Chiri village near Vapi

showed that the cod level was even more than the permissible

limit for industrial effluent, and the mercury level was about

90 times the prescribed limit.

Factories in vie deal with some very hazardous chemicals,

including pesticides and other agrochemicals, organochlorine

chemicals, dyes, acids like H-acid, liquid chlorine and chlorine

gas. Most of these substances have been banned in developed

countries. “In fact, a ban in the industrialised countries

is accompanied by a rise in manufacturing capacities of such

chemicals in countries like India,” says Michael Mazgaonkar

of PSS.

Gulab B Patel, a local leader in Chiri, says residents of

the village are using red-coloured water for the past seven-eight

years. “We have been drinking this water till recently.

But we launched a major agitation against gidc and forced

them to supply drinking water,” he says. For most other

purposes, people in villages near vie use contaminated groundwater.

Nearly 32 handpumps and 65 wells in the area reveal the presence

of chemicals, Patel observes.

Local people say the major source of groundwater pollution

is Rata Khadi, a seasonal stream near Chiri that carries effluent

from Vapi to a CETP. The effluents carry organochlorines,

heavy metals and other toxic chemicals. Patel says the colour

of the groundwater is the same as that of the effluents. In

1996, the villagers fought a case against gidc in the Gujarat

High Court, Ahmedabad, on the issue of groundwater pollution.

The verdict went in favour of the villagers. But, till today,

the situation remains the same, says Patel. In the past 15

years, CPCB and GPCB have taken groundwater samples from these

villages on several occasions. But no action has been taken

so far.

|

NANDESARI: The Nandesari

Industrial Estate (NIE) near Vadodara is a major production

centre for highly toxic chemicals, like h-acid, which are

not easily biodegradable. “Disposal of untreated mercury-contaminated

effluent from caustic manufacturers has heavily contaminated

groundwater in the Nandesari,” says a report submitted

by the Union ministry of environment and forests to the World

Bank.

NIE is situated along the Mini river, and has about 250 industrial

units dealing with chemicals, pharmaceuticals, dyes, pesticides

and plastics, among other things. A recent environment impact

assessment conducted by the National Productivity Council

(NPC) in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, says the groundwater has been

severely contaminated down to a depth of about 60 metres.

Water samples from a borewell dug by GIDC in Nandesari show

14.82 mg/l of lead, whereas water near the GIDC dump in the

area had 38.25 mg/l of lead. The permissible limit for lead

in drinking water is a mere 0.05 mg/l.

Reckless dumping of effluent and hazardous waste is as common

here as in other industrial areas of the state. About 80 companies

send their effluents for secondary treatment at the cetp in

Nandesari. Says a chemist employed at the plant: “Whenever

we find that effluents are not as per the required standards,

we do not allow them to discharge the effluents into the CETP.”

But there are more than 267 industrial units in the area.

The chemist says he does not know where other companies send

their effluents.

Kiritsinh M Gohil, sarpanch (head of the village council)

of Nandesari village, says: “Bad government policies

have made the area hell for the poor villagers. In the past,

several animals have died after drinking the polluted water,

whereas people have faced serious health problems.” Udaysinh

R Gohil, a resident of Nandesari, recalls that in 1965, GIDC

told farmers that once the industrial area is set up, their

earnings will increase by leaps and bounds as they will get

jobs and other benefits. But soon after a few chemical industries

were set up, crop production started decreasing, says Udaysinh

R Gohil, adding that most of the land in Nandesari is barren

now. He recalls that in 1982, severe water contamination was

reported in the area for the first time. But no effective

steps have been taken so far.

Ironically, instead of solving the pollution problems in the

region now, there are plans to increase the number of units

in the industrial area. “Authorities from the industrial

area have approached us several times to buy our lands,”

says the sarpanch of Nandesari. Pollution is bound to increase

in the absence of effective pollution control measures.

Killers

at Large

There are several industrial units in Medak district of

Andhra Pradesh (AP) that have directly or indirectly polluted

groundwater. AP Pollution Control Board (APPCB) officials

reveal that Reliance Cellulose is releasing effluents

with very high chemical oxygen demand levels into a nearby

stream. Standard Organics of Patancheru used to pump untreated

effluents into a nearby stream. Birchow, a pharmaceutical

company, was dumping sulphomethazole in the open. Today,

say APPCB officials, all these companies are meeting environmental

norms. “In fact, Birchow has acquired ISO 14001 certification,”

they point out.

Durichan Textile Mills was dumping untreated effluents

with high levels of sulphuric acid in an open stream 1.5

km away through a pipe. On July 17, 1999, APPCB found

hexa-valent chromate dumped alongside the roads in Patancheru.

After seeping into the groundwater, such pollutants can

be lethal to those who drink the water. There are five

units in the area that produce this waste, out of which

three have internal landfill sites. Tishya Chatterjee,

member secretary of APPCB, assures that the board will

soon catch the culprit.

APPCB officials also reveal names of some other rogue

units. They include Vantech Pesticides, Borin Laboratories,

Kaikule and Reddy Labs. Two companies, Global Drugs and

Saraka, were caught pumping effluents into a pond in Kazipally.

Saraka is still sending effluent tankers to a nearby pond.

Another company, Hetero Drugs, was caught dumping effluents

near a pond. |

How

did it go wrong?

The corrupt

and inefficient among pollution control authorities have

surrendered India’s groundwater to unscrupulous industrial

units.

“Industrialists believe it is cheaper to purchase

the regulators than abide by the regulations,” says

K Purushotham Reddy of the Hyderabad-based ngo Citizens

Against Pollution. “If I am not wrong, more than

90 per cent of gpcb officials are corrupt. In the present

circumstances, only God can save Gujarat from environmental

disasters,” says a cpcb official at Vadodara, adding

that this is the reason why polluting industries are operating

without a care for the environment.

While hearing a case against some h-acid manufacturing

units that had polluted the groundwater of villages near

Ratlam, Madhya Pradesh (MP), the mp High Court came down

heavily on the state pollution control board (SPCB): “The

interpretation put by the board... shows the collusion

of these officers. It was not expected of the MP Pollution

Control Board to have pleaded like this. It leaves a strong

suspicion that the pollution control board is not operating

objectively. The chairman should change all the officers

working in that area. We have strong reservation on their

working objectively and fairly.”

While all factories do not inject effluent directly into

the ground, they love to break the rules. In Gujarat,

several companies wait for heavy rains, when the production

levels of most companies increase to a great extent. The

reason is simple. “It becomes easy for them to dump

their effluents and wastes

anywhere they want. The effluents and wastes mix with

the rainwater and nobody raises any objection,” says

a CPCB official at Vadodara who did not want to be named.

If officials know this, what stops them from booking the

polluters? “Undue pressures from the political circle,”

says the official, pointing out that in the past seven

years, the board has not closed any industry in Gujarat

for polluting the environment.

Though it is very difficult to get senior officials to

speak openly about this, there is a growing realisation

of this fact among them. Says a senior scientist of PPCB,

“There are instances when some industrialists landed

up in our office to complain that the board officials

were demanding impossible amounts as bribe.” “The

extent of pollution problems in different states clearly

indicates that pcb officials are either not willing to

take action or they have connived with the polluters,”

says Rohit Prajapati. “There are wild allegations

against the pcb officials, and the way they tackle an

issue sometimes lends credence to such allegations,”

says M Mehta of CGWB, Chandigarh. I C Gupta, head of the

natural resources and development division of the Central

Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, who has studied

groundwater pollution in Rajasthan, says, “Our state

PCB is a dead body. Definitely, there is truth in the

allegation that the board officials are getting monthly

hafta (protection money) from the industries.”

Says D K Dua of PPCB: “Whether our officials are

corrupt or not it is to be confirmed, but as these officials

are from the state public health engineering department

on deputation, they are not really involved in their work.

This definitely affects the functioning of the board.”

Tishya Chatterjee of APPCB concedes his inability in booking

all the culprits. The board requires more power than what

it has at present, he says. “All 25 state PCBs in

India function as scapegoats for all concerned, being,

by default, the state-level repositories of all knowledge,

technologies, expertise and responsibilities,” says

Chatterjee. In the environmental management, government

regulatory agencies are weak at the impact level and decision

making is centralised. The victims of pollution have no

say at the decision-making levels, he adds. However, R

Rajamani, former secretary to mef, differs: “This

is not a matter of lacking powers, it is a matter of will,

which most pollution control board officials do not have.”

So, does India need another Bhopal disaster, which affected

600,000 people in 1984, to wake up the slumbering bureaucracy?

It is quite clear that pcbs have failed. Even if disaster

strikes, their reaction is nothing beyond knee-jerk reactions

like imposing a ban. Hence the onus of saving the country’s

groundwater resources rests in the hands of the people

of the country and the civil society. It is time for the

victims to become proactive. |

A

civil society pollution police?

The reason why local people and civil society can succeed

where pcbs have failed is that they are stakeholders in

groundwater resources. “It is not the PCBs who are

really affected by groundwater pollution but the people

of that particular region. So, the most effective strategy

would be to let the local people and the civil society

play a more active role in prevention of pollution,”

says Rajat Banerji, researcher at the New Delhi-based

Centre for Science and Environment.

Shalu Puri, programme officer at Voluntary Health Association

of India (VHAI), Delhi, underscores the need for public

pressure groups that can force industry to comply with

environmental norms. “Today, no pollution control

board can manage the problem unless the local people are

for it. They have to take interest in protection of their

environment and utilise the infrastructure provided by

the government for sustainable development,” she

says. But the civil society can only be successful if

the government ensures their right to information. “We

will have to push for political lobbying in order to formulate

acts so that the civil society can also be involved in

pollution control measures,” says Ravi Agarwal, director

of Srishti, a Delhi-based NGO.

Prajapati points out that most of the industrial units

in Gujarat are in rural areas where authorities cannot

constantly keep vigil. He says people are gradually losing

patience regarding increasing pollution levels. They are

already keeping a close watch on illegal dumping of wastes

in some industrial areas in Gujarat, which they are reporting

to gpcb, Prajapati observes. For example, a few factories

in Gorwa village of Vadodara district have been dumping

effluents in a sewer. The local people organised themselves

to catch the culprits. “They take photographs and

collect other evidence and hand these over to GPCB. People

are basically fed up with the approach of the industry

and pcbs. So they want to take action on their own in

order to control pollution. Such initiatives will prevent

GPCB from making excuses,” he says.

“In Western countries, the public boycotts products

from an industry which is found to pollute the environment.

In India, too, the civil society can not only pressurise

the pcbs but also force industries to abide by environmental

norms,” says A K Saxena, director, environmental

division, National Productivity Council, New Delhi. After

the 20th amendment to the Indian Factories Act in 1987,

the law makes it mandatory for every industry owner to

pass on information to common people regarding the use

of raw materials, types of pollutants coming out of the

industry and dumping of effluents, among other things.

And if any industrial unit does not comply with the norms,

the owner can face a sentence of seven years of imprisonment

under Section 92 of the Factories Act, 1948.

“But there is one problem with the civil society,

too. At many places, people’s groups and ngos raise

their voice against defaulting industries but withdraw

later after taking money,” says Sagar Dhara of M

Venkatarangaiya Foundation in Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh.

In Patancheru, for instance, the local people raised objections

during a public hearing against the setting up of an 18-megawatt

power project, he notes. “But the sarpanchs

withdrew their objections later. Such steps put the government

and investigating agencies in a quandary,” says Dhara.

This aspect should also be considered before advocating

the civil society’s role in pollution control measures,

Dhara emphasises.

But how do local people in industrial areas — silent

victims of pollution for years — take up the task

is the biggest challenge for the civil society. The voluntary

and non-profit sector has to mobilise people to shed their

fear and inhibitions. To convince them that their very

future is at stake. To convince them that it is now or

never. That without clean water, there is no agriculture,

no prosperity, no life. |

Double

whammy

Adulteration of milk is not a new

problem in the town of Bulandshahar in western Uttar Pradesh

(UP). However, it is leading to another type of slow poisoning.

Local people complain that dairies pump their effluents

containing urea and other chemical additives into the

ground.

“Some workers from a dairy came to me one day and

told me that they want to file a case against the particular

dairy as the owner threw them out without any reason.

In course of the conversation, they revealed that the

dairy is adulterating milk with urea and caustic soda

and all the effluents that are thereby produced are pumped

into the ground. They also named a couple of dairies nearby

who are doing the same,” says Anil Vats, a lawyer

in Bulandshahar.

The dairies use a lot of water in cleaning the equipment,

leaving large amounts of effluents, which are even more

dangerous in the case of dairies engaged in adulteration

and contain urea, caustic powder and colour additives,

among other things. With the town’s milk production

nearing one million litres, reports in the media say that

hundreds of litres of effluents are pumped into the ground

everyday. According to G S Yadav, regional officer of

the UP Pollution Control Board, Ghaziabad, the board has

closed down four milk-processing units as they did not

have effluent treatment plants.

Yadav acknowledges that the effluents can contaminate

groundwater as their biological oxygen demand is as high

as 800-1,000 milligrammes per litre (mg/l), while the

permissible limit for effluents is 30 mg/l. He adds that

the chemical oxygen demand and pH levels of effluents

are also considerably higher than is considered safe. |

“We

need a different approach”

D K Biswas, chairperson, Central

Pollution Control Board, interviewed about the seriousness

of groundwater pollution. Excerpts:

How

serious is the groundwater pollution problem in India?

Groundwater pollution is very

difficult to evaluate as till now, there is no nationwide

survey or study of it except the few studies done by

CPCB. On that basis I can say that it is very serious

and needs special attention.

Why has

groundwater pollution not got its due attention?

It is partly due to lack of awareness

among people and policymakers and partly due to the

backlog of inaction in averting this pollution. Till

now the general belief among people is that groundwater

is pure and can be consumed straight. The reality is

totally the reverse of it — groundwater is now

not fit for drinking without any treatment. This is

also causing lots of health problems.

It is the same problem with the policymakers. Recently,

when I was talking to a senior Union minister regarding

pollution of the Ganga, his reaction was: “Ganga

is sacred and cannot be polluted.” This is the

attitude towards surface waterbodies, when we can all

actually see how polluted are they. So, groundwater

is never

considered to be polluted, though most of the groundwater

is affected by pollution, both natural and human-made.

Only in the past five-six years have we started paying

attention to groundwater pollution. To begin with, we

have earmarked 22 critical sites all over the country.

The result is frightening, and it is my belief that

we will get more shocks in the future.

What are

the reasons for groundwater pollution?

The primary reasons are industrial

pollution and extensive farming leading to agrochemical

pollution of the groundwater. In case of industries,

it is due to lack of treatment of effluents that are

pumped into rivers and streams leading to groundwater

pollution. Even

if there is facility for treating effluent, industries

do not have the proper drainage systems for treated

effluents, which again leach into the ground. It may

be noted that treated effluents also carry toxic contents.

You see the Gujarat belt; thousands of industrial units

have been polluting groundwater for years.

Similarly extensive farming has caused agrochemical

pollution of the groundwater. Nitrates and DDT are two

major hazardous chemicals that farming adds to groundwater.

Besides this, there is natural pollution, like fluoride

and arsenic contamination due to overexploitation of

groundwater. Delhi has a high level of fluorides due

to overexploitation, while it is natural arsenic contamination

of groundwater in West Bengal.

Then are

you going to penalise the groundwater polluters more

than those who pollute the air?

The present

laws do not differentiate between surface and groundwater.

And CPCB and the state pollution control boards do not

have the power to penalise the polluting industries.

We need a different approach to groundwater pollution.

Are you suggesting

different rules and regulation for groundwater pollution?

Yes. Even the Central Ground Water

Authority (CGWA) has

suggested a new legislation to deal with groundwater.

We have suggested to the ministry of environment and

forests to give more powers to CGWA as suggested by

the Supreme Court. Even so, CGWA has enough power to

stop extraction of groundwater, which can help curb

the spread of polluted water.

|

No way

back

Once polluted by industry, groundwater

is very difficult to clean up. This is the lesson learnt

from the Bichhri experience. Situated about 12 km from

Udaipur, the groundwater of Bichhri, spread over an

area of 300 hectares, is stark red. And as the groundwater

moves naturally to other aquifers, it pollutes that

water as well. Seventy wells used by some 10,000 residents

have been rendered completely useless, and the 22 villages

are without any drinking water now. In 1983, an H-acid

manufacturing unit ruined the groundwater — seemingly

forever.

After a 1996 order from the Supreme Court (SC), officials

of the Union ministry of environment and forest (MEF)

and other state departments concerned have tried hard

to clean up the water. But it seems virtually impossible,

mainly for two reasons: firstly, cleaning groundwater

is very difficult, and, secondly, even if it is possible,

the cost is prohibitive. The cost of cleaning the polluted

water of Bichhri is estimated at Rs 40 crore. SC ordered

the clean-up of groundwater after auctioning the factory’s

property. This came to a miserable Rs 5,00,000.

“Cleaning the water of Bichhri is just impossible.

Like the H-acid (which is used in dyeing and does not

allow the colour to fade), the groundwater polluted

by it also refuses to its shed colour,” says Kishore

Saint of the Udaipur-based non-governmental organisation

Ubeshwar Vikas Mandal, which helped in bringing the

Bichhri case into the limelight.

In 1990, SC ordered de-watering of the affected wells

to clean them. The Rajasthan Pollution Control Board

opposed this on two grounds. Firstly, after de-watering,

the wells had to be filled with freshwater, which was

unavailable. Secondly there was no feasible method to

clean the polluted water, which, if dumped, could pollute

further. “Till now, we have not decided exactly

how to clean the polluted water,” says Tapan Chakravarty,

deputy director of the National Environmental Engineering

Research Institute (NEERI), Nagpur, which has been assigned

the task of cleaning the water. “It is going to

be a very difficult affair. That is why pollution of

groundwater is serious,” says Chakravarty.

|

What goes down must come up

August 31, 1999 |

|

|

|

|